The Archeological Discoveries at Igbo-Ukwu

(History)

The Igboman is used to be regarded as without a history. The Yoruba had until the recent discoveries and archaeological excavations made by Prof. Thurstan Shaw at Igbo-Ukwu felt that they were the only race in Southern Nigeria with a history. This feeling was based on Ife arts and cultures, which were in vogue at the time the Europeans first set their feet on Nigerian soil. Recent developments in Igbo-Ukwu have proved this assertion null and void. It now has been proved that as the Yoruba and Bini arts and culture flourished during the advent of Western civilization because the Onis and Obas were still holding their sway as powerful rulers, the great rulers in Igboland were at their wane. Empires rise and fall. This does not mean to assert that there has been some great civilization in the area, which has fallen, but the research and excavations made in Igbo-Ukwu have proved the existence of some great culture and society in antiquity. The current ruler of the Yoruba in Nigeria, Oba HRH Adeyeye Enitan Ogunwusi, Ojaja II, the Ooni of Ife, has averred that homo sapiens made his first appearance in Igbo land, thereby asserting that Igbo is the origin of mankind. Perhaps, therefore, the Israelites may have come from Igbo land rather than the other way around, which people had often assumed. The Ooni also asserted that his kingdom was initially conquered by the Igbo until they were rescued by Moremi, he also confirmed the presence of an aboriginal Igbo community that still exists in Ile Ife to this day. The Igbo people who founded or were part of the founding of the Yoruba kingdom must have inspired the Ife arts and culture. The Ugbo people of Ondo State have the same Obatala linkage with the aborigines of Ile Ife. There is also this narrative about the Igbo people who were part of the founding of the Benin Kingdom and perhaps who taught them the bronze casting and iron smiting culture. These narratives have a lot of evidence behind them.

Archaeological finds in Igbo-Ukwu give proof to the fact that the Igboman has an immense history. These finds, according to archaeologists and anthropologists date earlier than Yoruba and Benin arts and culture. Antiquities of West Africa have been dated as follows:

The Nok culture, regarded as the earliest in West Africa, dates from 900 BC to 200 AD. This is followed by the Igbo-Ukwu culture of the 9th century. Ife culture comes next starting from the 12th century to the 15th century. Owo culture of the 15th century was followed by Bini culture starting from the 15th to 19th century. Tsoede and Esie cultures are the latest dating from the 16th to the 18th centuries respectively.

The archaeological remains in Igbo-Ukwu are a true indication of the existence of a rich well-organized society under powerful political rulers at the heart of Igboland hundreds of years before the coming of the Europeans. Germans who are the Aryan race claim to be the origin of man on earth, while according to the Bible, man started life in the Garden of Eden from which later, God made the Israelites His chosen people. Historians and anthropologists on the other hand hold that man evolved from the African continent probably in East Africa some four million years ago. The earliest culture in the world, in Oldowan, evolved in the same place and it was then that man began his bicultural evolutionary development (handyman). Coming down to Southern Nigeria, the Yoruba talk of Oduduwa, thereby claiming that Ife is the origin of man. This assertion is supported by the Ife arts and culture but this is not to say that this claim is factual. Coming home a little further, the Nri culture claims that Eri came down from heaven and settled at Aguleri through the help of an Awka blacksmith, and with some artefacts to show. However, that claim does not suffice for the origin of the entire Igbo race, but for the children of Eri alone. The finds in Igbo-Ukwu, which date many hundreds of years earlier than Ife arts and Eri culture should have shaken the Yoruba and to a greater intensity, the Nri. These finds in Igbo-Ukwu must as a matter of fact bring a complete transformation in Igbo, West Africa and African history.

Many possess very scanty knowledge about the archaeological finds in Igbo-Ukwu and very few, especially in this modern era, have come in contact with the work of Prof. Thurstan Shaw on these finds. His works were published in the 70’s and were available mainly to the elite at the time. Although they could be found in older libraries like the University of Nigeria Nsukka Library, the University of Ibadan, now Obafemi Awolowo University, and in some National Archives, they are currently classified as archival materials which are not easily accessible to ordinary folks.

Shaw’s Work at Igbo-Ukwu

The very stroke that instigated the work of Shaw at Igbo-Ukwu was the discoveries made by Isaiah Anozie during the month of December, before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, when he was digging a cistern. The cistern is the traditional way of preserving surface water for use during the dry season because of the water difficulties experienced by people in this area during the dry season. Such cisterns are almost phased out because of the advent of pipe-borne water supply and other methods of water supply. Mr Isaiah discovered quite a number of items when he was digging the cistern. Ignorant enough, he only used them in decorating his sitting room and sold the rest to his neighbours and people who felt they could be potent or good for making charms. It was through the help of the District Officer who was enlightened enough and who realized the importance of such artefacts when he became aware of them that the Department of Antiquities came to the knowledge of it.

“At this point in time, the town in which the discoveries were made was referred to as ‘Igbo’ and this is the name marked on most maps. It was later that the suffix ‘Ukwu’ was added to it, i.e. Igbo-Ukwu meaning ‘Great Igbo’ – to distinguish this place from other places called ‘Igbo’. The name Igbo-Ukwu became increasingly necessary since linguists are using the same spelling ‘Igbo’ for the name of the people who live in this part of Nigeria and for the language they speak. No other town had been known and called by this name ‘Igbo’. There are towns with the word in their name but right from the onset, these towns had some prefix or suffix originally attached to their names. None of them like Igbo-Ukwu had from origin been solely and purely called Igbo.

When Professor Thurstan Shaw arrived in Nigeria from London in November 1959 following the invitation of 1958, he began with a number of visits to the cultural centres in Nigeria and contacts with relevant individuals. He arrived at Igbo-Ukwu and made the necessary negotiations that would guarantee his freedom to work. When everything was ready, he made excavations at three different locations, first, in Isaiah Anozie’s and in Richard Anozie’s compounds in 1960. Later, he returned to make further excavations in Jonah Anozie’s compounds in 1964. These men are notably, indigenes of Igbo-Ukwu.

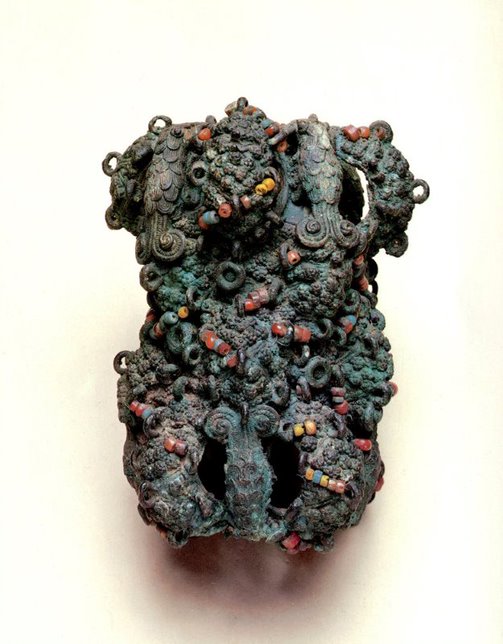

The results of the excavations were highly revealing. The result of the first digging in 1960 in Isaiah’s compound interpreted to be a storehouse for regalia’ revealed over 50 different items made of bronze, brass, copper, iron, clay, ores and several heaps of beads. They were significantly made by very highly experienced artists through sophisticated and complicated processes.

The items disclosed include:

- Bronze roped pot

- Bronze alter stand

- Heap of Iron knives

- Globular pot with stopper

- Copper spiral snake ornament

- Collapsed globular pot with stopper

- Pottery overlying bronze bowl

- Smaller bronze bowl

- Longer bronze bowl

- Plagues of composite belt

- Mass of copper wire

- Pedestal pot on its side

- Mass of beads

- Rows of beads

- Beads

- Iron sword blade in two pieces

- Copper scabbard-support

- Bronze pendant ornament (elephant head)

- Associated rows of beads

- Associated crotals

- Copper ring

- Spiral-headed copper staples

- Bronze crotals

- Rows of fine spiral copper bases

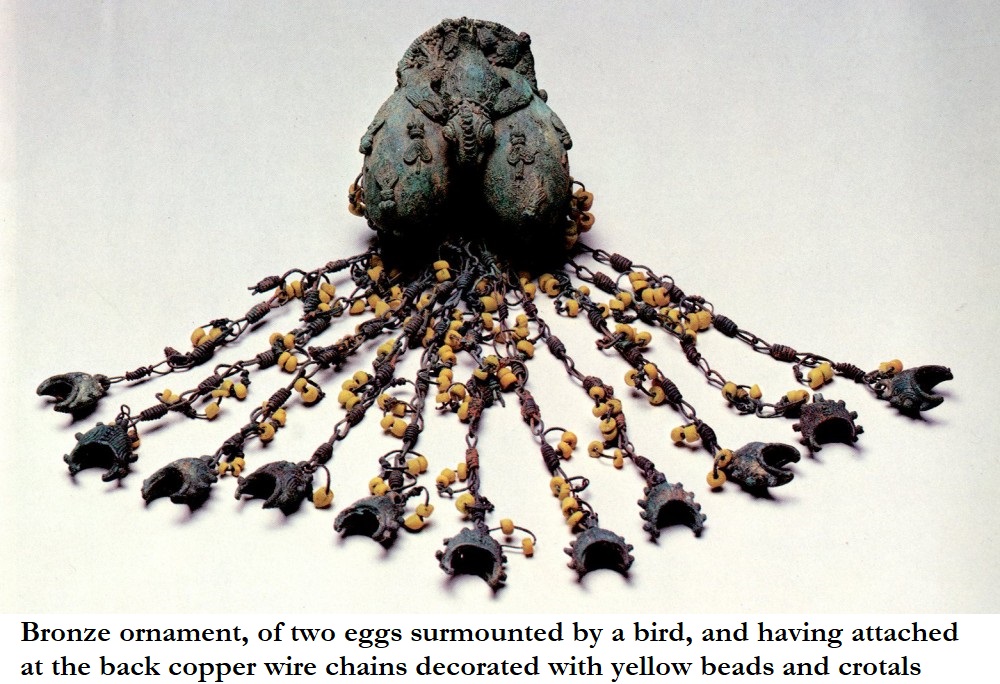

- Bronze pendant ornament (double egg)

- Beads and Copper wire attached to the pendant ornament

- Semicircular copper handle for calabash

- Semicircular copper handle for calabash

- Bronze shell

- Copper handle for calabash

- Bronze staff head

- Iron blade associated with staff head

- Iron objects

- Iron objects probably calabash fittings

- Ring of dark substance inside rings.

- Three copper rings

- Copper handle for calabash

- Pieces of Calabash

- Decorated pieces of calabash with a copper handle attached

- Part of copper handle for calabashes

- Human molar tooth

- Pieces of cloth

- Pieces of Bronze chain

- Broken lower end of a Bronze sword scabbard

- Copper handle for calabash

- Four bronze canine teeth

The list excludes the number of items already dug out by Isaiah himself while digging a cistern. Though some of these items were sold, some have been recovered among which is a bronze pendant ornament in the form of a leopard’s head etc. Some others were never recovered.

The digging in the compound of Mr Richard Anozie the same year was understood to be a burial chamber of a titled man or a priest-king. Among the disclosures made from this chamber were many different items, which include:

- Northernmost elephant tusk

- Decorated copper roundels

- Crown

- D-shaped decorated copper plate

- Pectoral plate

- Copper bracket

- Copper anklet

- Copper Strap

- Skull

- Pair of Copper anklets

- Circle of spiral copper bosses set in wood

- Copper and bead anklets

- Another part of copper

- Copper handle for a calabash

- Middle elephant tusk

- Tangled copper fan-holder

- A group of six copper anklets

- Group of three copper anklets

- Another copper bracelet

- Copper staff supporting the bronze leopard’s skull

- Bronze horseman hilt

- Southernmost elephant tusk and many pieces of iron.

Among the items revealed at this spot were:

- 15 copper or bronze wristlets

- Four heavier copper wire

- Copper rod, some 15cm long

- Iron funnel

- Small bronze bell

- Large crotal with two chain links attached

- Broken top of another small decorated bell

- Two cylindrical staff ornament

- Paper-thin casting of a similar cylindrical ornament

- Two copper bars with expanded ends

- Lots of pottery etc.

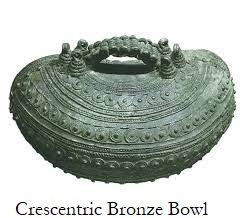

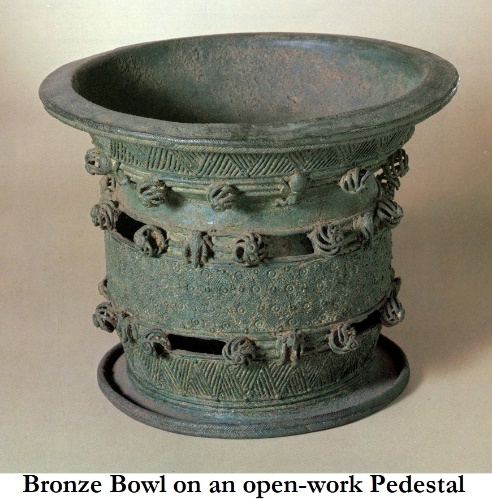

According to Thurstan Shaw, one interesting thing about the bronzes found at Igbo-Ukwu was that their style and decoration were quite unlike the well-known bronzes of Benin and Ife. It shows the exclusivity of the cultures from each other and the difference in age (time). There was no way a comparison could be made between Igbo-Ukwu culture and the other two cultures. The findings at Igbo-Ukwu being also scientifically and artistically superior demand a new channel of inquiry. If ever there was any connection, the bronzes of Benin and Ife should be a product of an apprentice to the Igbo-Ukwu artists or an effect of deterioration of the principles of the art over a very long period of time. Analysis of the items from the diggings by Shaw shows that the bronzes were original to the area and the people presently occupying the land; they were true of Igbo-Ukwu and Igbo culture. For instance, it is clear that the bronze pot had been made in the pattern of most of the Igbo-Ukwu pieces still in use in the area, “Ite-otu”, a globular pot used in storing palm wine, water or used as a resonator in music of a dance concert.

Although the bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu were made in the same method as Benin and Ife bronzes i.e. by the lost wax method, the Igbo-Ukwu bronzes display much higher sophistication and complexity, showing a wide degree of disparity between the producers of the cultures. The principle of the lost wax method is simple, although its execution can be very complex and call for a great deal of skill and creativity. The principle is to make a model of wax and then replace it with bronze. This is because wax can be easily modelled into any desired shape. The procedure goes from modeling wax into any shape and removing over fire through a hole. When bronze is heated sufficiently, it becomes molten and can be poured into the mould through a hole, where it will set hard in the shape of the mould. The clay is then removed. To be able to perform this process, the Igbo-Ukwu metallurgist knew the exact properties or behaviour of the different metals and materials they used.

The procedure of the lost wax is used for casting solid objects such as the belt plague which is found in Isaiah’s compound. Again, the metallurgists seemed to have understood the principles and need for conservation of materials, because, for the making of larger objects, a clay core has to be used to make the casting hollow. This surely, was in order to save wasting metal, but on the other hand, this technique makes the procedure more complicated. The core of clay is modeled roughly to the shape of the inside of the desired object, and mounted on a clay pedestal or base. The core is then covered with a large layer of wax, which now receives the details of shape and pattern ultimately desired for the bronze object. The whole mould is covered with clay and wax melted off through pouring duct created by adding a rod of wax. The bronze is melted and poured into the mould through the pouring duct and allowed to set.

Some of the bigger and more complex bronzes, like the Bronze Roped Pot, were not cast in one piece, they were cast in combination of processes. These procedures reveal the complexity in such molding, which is described elaborately by Thurstan Shaw in his work: Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu. From this description as well, it is realized that in the lost wax method, each can only be used once resulting in the uniqueness of each casting. The complexity of the designs and pattern used in decorating these items were immense and unique in character and over 63,200 beads were found in Isaiah’s compound, many of them lying in rows. Among the findings were also spiral snake ornaments which consist of a square sectioned spike of copper running through a spirally coiled length copper and which terminate in the snake’s head, holding an egg in its mouth. These decorations were not made by being molded in wax before casting, but were achieved with a sharp-ended punch hammered into cold metal. It is remarkable that analysis has shown that objects from Igbo-Ukwu made in this fashion are composed of almost pure copper, while the objects made by the wax casting process are composed of bronze. What is interesting about this is the indication it gives to us of the metallurgical knowledge of the craftsmen who made the metal objects of Igbo-Ukwu. Copper can be bent, twisted, inscribed and have designs punched into it in a cold state much more easily than bronze, while bronze flows more easily when molten and is better for casting than copper. This is an indication that the Igbo-Ukwu metallurgists were scientific enough to understand these properties, and as such, knew what they were doing.

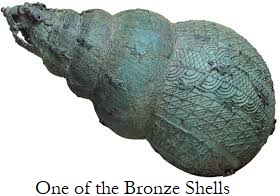

There were a number of fascinating and interesting items found in the diggings. Thanks to the expertise of Shaw who split his hairs in interpreting and fitting the broken items together to obtain the pictures very close to reality of them. Among the items he discovered the staff ornaments, which were among the most complex and most highly decorated of all Igbo-Ukwu casting (details in Shaw’s work “Unearthing Igbo-Ukwu). He also tried to situate some of these items in history, in the process of this attempt, he discovered the bronze casting of shell, which was assumed to be in imitation of the giant Africa land snail; Achatina.

However, no less than four different experts on shells to whom photographs have been shown concur in the opinion that it is a triton shell (Charoina), which is represented in each case. The coast where such shells occur is only 180kilometer (100 miles) away, but the identification of the form of these bronze vessels with that of a seashell may well have important implications.

It may therefore have the implication that Igbo-Ukwu culture has influence or contacts that extended beyond the immediate environment. Again, the two human head ornaments are among the most attractive casting from the digging. They bear the same pattern of facial scarifications radiating in four directions from the bridge of the nose, which are the same pattern with the human heads decorating one of the cylindrical staff ornaments. This is clearly in resonance with the age long and dying practice in the area called “Ichi”. The heap of knives must have been the objects used in performing this delicate scarification ritual. Furthermore, a number of animal heads such as the leopard head, snakes, snails, python, monkeys, elephant tusk etc. form little or no basis for speculations on the nationality of these items except to believe that they belong to the people among whom these finds were made.

The rest of this segment could be read from the work on Igbo-Ukwu.